Steppes and deserts - Extreme habitats

Protecting biodiversity on the edge

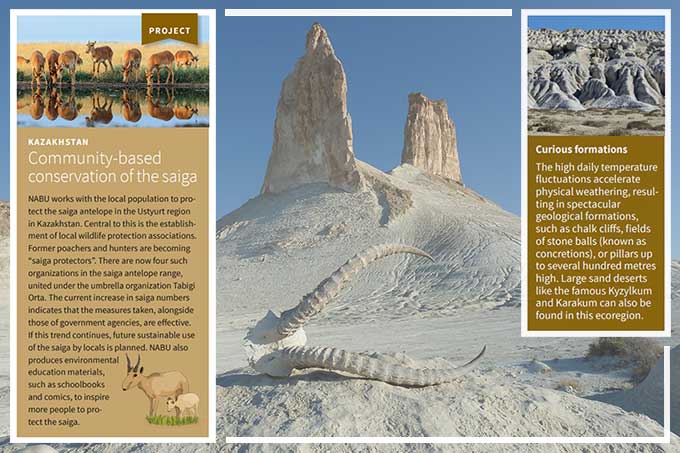

The Ustyurt Plateau in Kazakhstan - photo: Tatiana/ stock.adobe.com

Numbering among the driest areas of our planet, steppes and deserts are shaped by the unique climatic conditions of their inner-continental locations. Wide landscapes and extraordinary geological formations characterize these barren ecosystems. They are mainly located in Eurasia, where they stretch from the Black Sea to the north-eastern parts of China. But temperate steppes can also be found in the Great Plains of North America, mostly referred to as prairies, and in small patches of Patagonia and the southern Andes, where they are called pampas.

Cold winter steppes and deserts

In Central Asia, cold winter (or temperate) steppes and deserts are by far the dominant ecosystems, covering about two thirds of the land surface. Here, the view stretches almost uninterrupted to the horizon, due to the mostly flat or undulating landscape, where trees are absent and large shrubs are rare.

Extreme climatic conditions and sparse vegetation are typical in these ecosystems. Temperatures can drop to -40°C in winter and rise to over 50°C in summer. The landscape is mainly characterized by clay and loess soils, and as the precipitation only stays on the surface and evaporates quickly, this creates dust and increases aridity.

While the steppes are dominated by herbs and grasses, the deserts favor wormwood, dwarf and semi-shrubs and succulent species. To adapt to the dry climate, larger shrubs such as the saxaul form relatively small stands on sand as well as in moist areas. The fauna of the region consists mainly of small rodents, such as jerboas and ground squirrels, and large herbivores, like the saiga antelope and goitered gazelle. Here, every life form has had to adapt to the harsh conditions and become a survival specialist.

Fragile ecosystems under pressure

However, even the most adapted survival artists are struggling in the face of increasing anthropogenic influence. Intensive farming, grazing, poaching and infrastructure expansion are putting the ecosystem under pressure. In recent years, additional gas and oil pipelines as well as roads and railroads have been built through the steppes and deserts of Central Asia. Along with barbed wire fences, for example along the borders of Kazakhstan, these linear structures pose serious obstacles for animal migrations. Extensive poaching of birds and mammals remains a major challenge in these vast landscapes, which are difficult to monitor.

Historically, the semi-nomadic lifestyles of the local population, such as the Kazakh tribes, allowed humans and nature to coexist. However, this balance ended abruptly with the collectivization campaign of the Soviet Union in the 1930s and the subsequent forced sedentarization of the semi-nomadic tribes. By the 1960s, most of the northern steppes had been ploughed under to grow crops, such as durum wheat. Today the expansion of agriculture and grazing continues to degrade the landscapes and poses a major threat to large ungulates such as the saiga antelope. They are losing their summer pastures and habitats to agricultural areas and are driven away by farmers trying to keep them off their crops.

As a result, wildlife has drastically declined in the region and you can often travel for hours without seeing any large animals. The only abundant species are rodents like steppe marmots, gerbils, ground squirrels and crepuscular jerboas. Occasionally saiga antelopes and rarely goitered gazelles or kulans (Asiatic wild asses) can be observed. Others, such as wild horses and camels, went extinct over a century ago. The same fate was met by the iconic Asiatic cheetah, which hunted goitered gazelles and saiga antelopes in Central Asia until the middle of the 20th century. Evidence of the former abundance of wildlife in these ecosystems is provided by hundreds of so-called 'desert kites', ancient stone-and-dirt structures which were used by Neolithic hunters to hunt ungulates in large numbers.

"With recovering saiga numbers, local communities fear damage to their fields and pastures. To increase acceptance for them, we help develop economically attractive sustainable use."

Stefan Michel, Project Coordinator Saiga Protection

The Ustyurt Plateau

In the tri-border area between Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan lies the Ustyurt Plateau – one of the last places of refuge for various species, some of them rare and endangered. Urials (a type of wild sheep), goitered gazelles, honey badgers and desert lynx find a home in these extreme landscapes even today. Single leopards also irregularly cross the Turkmen border into Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. In the north of the Ustyurt Plateau, deserts covered with dwarf shrubs merge into vast grassy steppes. Feather grasses sway in the wind and saiga antelopes populate these landscapes in growing numbers. To the east, the plateau borders the largely dried-up Aral Sea, on whose former lake bed herds of kulans can still be observed. Today, brine shrimp also reproduce in the increasingly salty water. This in turn attracts flamingos, for which brine shrimp are the preferred food source.

Access to water in these arid ecosystems is especially important for domestic and wild animals. Precious water holes, at the foot of chalk cliffs up to 150 metres high bordering the Ustyurt Plateau, allow the animals to survive in this arid landscape. The cliffs are remnants of a coastline of the Tethys Sea, which existed here in the Mesozoic, 250 to 66 million years ago. Numerous fossils of marine animals, including shark teeth, sea urchins and shells, bear witness to this period.

Humans also live in the dry steppe and desert region of the Ustyurt Plateau. In the arid climate, the local population almost exclusively raises livestock such as camels, horses, cattle, sheep and goats, while the northern steppes are partly used for agriculture. While parts of the region are under the protection of nature reserves, such as the Kaplankyr Nature Reserve in Turkmenistan and the Ustyurt Nature Reserve in Kazakhstan, human activities are expanding onto the Ustyurt Plateau and endangering its ecosystems and wildlife.

Resilient yet fragile: the desert and steppe ecosystems of Central Asia - image: Victor Tyakht/ stock.adobe.com, NABU/ Til Dieterich, Julia Friese

Protecting the last places of refuge

Since 2014, NABU has been increasingly alarmed by reports of the rapid decline of saiga antelopes and the ongoing development of the Ustyurt Plateau for oil and gas exploration. This has prompted NABU to advocate for the protection of this unique habitat and its iconic species and to campaign for the Ustyurt Nature Reserve to be designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A challenging mission, as there were plans to develop gas fields in the immediate vicinity of the nature reserve. With the combined efforts of local partners, NABU succeeded in persuading the government to abandon this project. Currently, there are even plans to expand the 230,000 hectares Ustyurt Nature Reserve by up to 600,000 hectares – a glimmer of hope, as this would ensure long-term protection for a particularly valuable part of the Ustyurt Plateau.

NABU and its experts work actively with local communities in the Ustyurt region to protect the saiga antelope from extinction. By supporting the establishment of local wildlife protection organizations, we aim to prevent poaching, protect habitats and restore the population of the saiga antelope. These efforts have been successful: based on aerial surveys, the population of the species in the Ustyurt region had recovered to 12,000 individuals in 2021. This local species conservation work is not only helping one of the oldest mammal species in the world; it is also preserving the ecosystem of the steppes and deserts from degradation. The steppe needs the grazing herds: the ungulates fertilize it, spread plant seeds and keep the grass short, thus restricting wildfires and providing ideal habitats for other species, such as the sandgrouse or the endangered saker falcon.

SELECTED PROJECTS

The goitered gazelle inhabits Asian steppes and semi-deserts from the Arabian Peninsula to northern China. The little gazelle was once at home in Kyrgyzstan too, but has become locally extinct. NABU is supporting a project to reintroduce this species. more →