Forests - The heart of biodiversity

Fighting deforestation is key

Fighting deforestation is a key component of preserving biodiversity. - photo: Davide Bonaldo/stock.adobe.com

These critical biomes can be found in different regions of the world, from the tropics and subtropics to the boreal and temperate domains. They provide important ecosystem services and goods, not only to the people living in and around forests, but to everyone on the planet. Indispensable forest products include wood, fruits and ingredients for medicines. In addition, ecological functions such as the purification of water and air, disaster mitigation, climate regulation and carbon storage are of global importance for securing healthy environments and fighting the climate crisis.

Many local communities and indigenous groups directly depend on forests for their livelihoods and food security. For about one billion people globally, wild foods provided by forests are an important part of their diet, and are often a key source of vitamins and trace elements. In addition, forests provide employment to more than 80 million people in the informal as well as the formal sector. The social and cultural benefits of forests, including recreation and spirituality, are also increasingly being recognized as important.

"Forests are so much more than just trees – they provide us with essential ecosystem services and are a real safety net for many impoverished families around the world."

Svane Bender, Deputy Director International Affairs / Head of Africa Programme

How much biodiversity is found in forests?

It is uncontested that forests provide a home to a large number of living organisms in the soil, understorey and canopy. It is often stated that 80 percent of all terrestrial flora and fauna can be found in forests, but such numbers can only be seen as a very rough estimate, since new species are still being discovered and there is considerable uncertainty about how much more remains undetected.

Of the almost 70,000 known and described vertebrate species, 80 percent of all known amphibians (almost 5,000 species), 75 percent of all known birds (almost 7,450 species) and 68 percent of all known mammals (more than 3,700 species) live in forest habitats. Of the 1.3 million invertebrate species described, many are insects, the vast majority of which also lives in forests. Since much of the soil biota, including bacteria and fungi, is probably still unknown to science, its abundance in forests (both absolutely and in comparison to other ecosystems) is even more difficult to estimate.

Biological diversity is not evenly distributed among different forest biomes. It depends on factors such as forest types, geography, soils, climate and also human activities. Tropical forests are particularly diverse, with about 60 percent of the 391,000 known species of vascular plants. Boreal forests in comparison display a much lower diversity of both plants and animals, with only about 20 different tree species, for example.

Forests under threat

Forests are home to countless species, such as the mantled guereza, native to Africa - photo: Bruno D\'Amicis

Unfortunately, about one third of the more than 60,000 known tree species are already globally threatened, with more than 1,400 even listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The biggest threats to forests and their biodiversity are deforestation, forest fragmentation and degradation. While global deforestation rates dropped in the five years between 2015 and 2020 compared to the 1990s, the ongoing destruction – especially of the highly biodiverse tropical primary rainforest – is still alarming. In 2020, an area of humid tropical primary rainforest approximately the size of the Netherlands was destroyed, an increase of twelve percent compared to the previous year.

Ongoing forest destruction not only threatens these important habitats, but also leads to increased fragmentation of remaining forest areas. Fragmentation not only negatively impacts the movement and dispersal of forest species, but also increases the number of forest edges with altered habitat properties. Degraded forests are disturbed ecosystems which are unable to function well or to provide vital ecosystem services and goods to people and nature. In addition, they are less resilient to disturbances such as diseases and natural disasters.

The main drivers of forest degradation, overexploitation and fragmentation, are of human origin and include the expansion of agriculture, the excessive extraction of goods such as wood, infrastructure development, the exploitation of natural resources, pollution, and the introduction of invasive species. Even though forest fires are naturally occurring events, fire seasons are becoming more intense and widespread as a result of climate change. For example, previously unaffected tropical rainforests are drying up, making these degraded ecosystems susceptible to fires. Besides the aforementioned threats, which affect the whole forest ecosystem, threats to single species from poaching and wildlife trade can have substantial impacts on population numbers in a given region – ultimately leading to extinction.

NABU preserves, restores, and conducts research throughout forests in Africa and Southeast Asia - photos: Forest Protection Team/Hutan Harapan, NABU/Maheder Haileselassie, sculpies/stock.adobe.com, Julia Friese

Close collaboration with indigenous peoples

Forests are of global importance but need to be protected on a local level, involving the people depending directly on them. For a long time, forest conservation neglected the importance of forest ecosystems for local communities and indigenous peoples. Since any human activity in protected areas was perceived as undesirable, and as counteracting the goal of returning forests to their “wild” state, many people were displaced and denied access to their ancestral land. In addition, the value of their knowledge about the forest and its biodiversity has often been underestimated.

Today, the involvement of local communities and indigenous peoples has largely been acknowledged as an integral part of successful forest protection projects. Recognizing the importance of stakeholder engagement, NABU always works closely with local communities and indigenous peoples as well as local staff and partners during every stage of a project, from project design to implementation. In those partnerships, NABU also supports capacity development of local communities and local government representatives in different aspects of sustainable forest management.

Empowering communities for conservation and sustainable livelihoods

With projects like AfriEvolve, NABU and its partners teach sustainable agriculture based on integration with healthy forest ecosystems instead of deforestation. - photo: SOS-Forêt

To help local communities generate income from activities that do not harm forests and their biodiversity, NABU actively promotes commodity development within its projects. Examples of forest goods being produced and sold include coffee, cacao, fruits, honey, herbs, and spices. Moreover, NABU promotes participatory forest management (PFM), enabling local forest communities to take over the management and conservation of forests while at the same time securing forest access for forest-dependent communities. For the conservation of forests, NABU joins forces with relevant institutions and stakeholder groups, such as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the Indonesian BirdLife partner, Burung Indonesia, or the KfW German Development Bank.

As forest destruction poses the biggest threat to the biological diversity found in these ecosystems, patrols are conducted to prevent encroachment and the conversion from forest to farmland, and to detect and fight fires at an early stage. Restoration work is carried out on degraded and cleared lands, with the main aim of creating conditions under which forests can recover by themselves and support the organisms living in them. Where needed, trees are planted to create buffer zones and close gaps between forest patches. NABU’s forest projects focus not only on protected areas, but also on the important areas in between to secure vital corridors for species.

Many of our forest projects are located in biodiversity hotspots in Africa and Southeast Asia, where inventories of species are still highly incomplete. Understanding species population dynamics is crucial for assessing and improving management practices. NABU therefore organizes and conducts assessments of species and biodiversity and is involved in designing and implementing long-term biodiversity monitoring systems and species action plans.

SELECTED PROJECTS

The project Green Change builds the resilience of people and nature in times of climate crisis. Our work in the Yayu Biosphere Reserve supports sustainable land use, the planting of old varieties and the empowerment of women and youth through generated income. more →

NABU and six African NGOs are setting up regional cluster networks for enhancing organisational development of green NGOs in Africa and supporting local farmers in adapting agricultural systems to climate change. more →

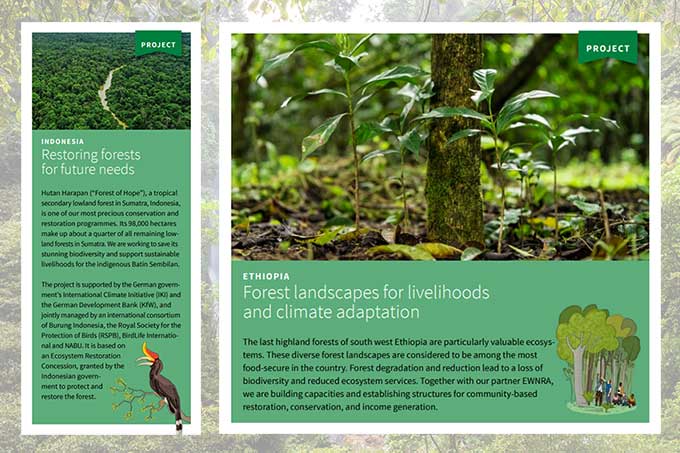

Hutan Harapan, the "forest of hope", is a tropical lowland forest in Sumatra, Indonesia, and one of our most precious conservation and restoration programmes. The forest is one of the last refuges for endangered species and provides countless ecosystem services. more →

Kafa Biosphere Reserve is challenged by the lack of sustainable employment and innovation for green development and adaptation to the impacts of climate change. The project aims at structuring the up to now non-commercialised garden coffee value chain. more →

The protected area Mahavavy-Kinkony in Madagascar suffers from degradation of its coastal ecosystems. NABU and ASITY Madagascar joined forces supporting communities for restoring ecosystems, improving livelihoods and responding to the impacts of climate change. more →

Degradation of highland forest landscapes of South Ethiopia is a serious threat to livelihoods and biodiversity. NABU is engaged with the goal of preserving the forests of Bench-Sheko, Kafa & Sheka as carbon sinks and long-term ecosystem service suppliers. more →

Ethiopia currently caters for 96 percent of its energy requirement using biomass. Due to this fact, many households satisfy their demands by collecting wood from the available natural forests which has been identified as a major driver for deforestation. more →

Like many-fingered hands, their roots reach underwater, finding a hold in muddy soils. But what happens when there’s nothing to hold onto? Mangrove forests are under massive pressure worldwide. Conservationist Patma Santi tells us how to save them. more →